For many young adults, the idea of getting onto the property ladder can feel more like a fantasy than a plan. Rents are high, wages feel stuck, and saving a deposit often seems impossible unless something drastic changes. That pressure is exactly what led one 25-year-old man to ask a difficult and deeply personal question: should he move into his ill grandmother’s basement to save serious money, even though it could all fall apart suddenly?

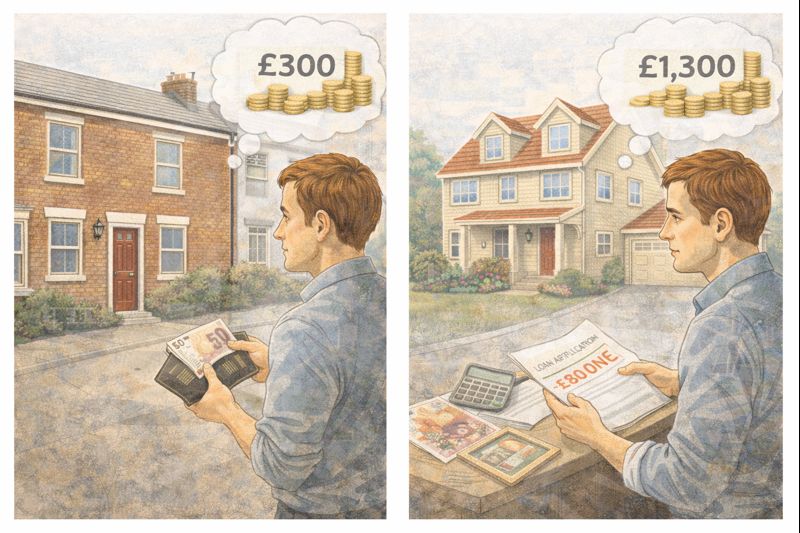

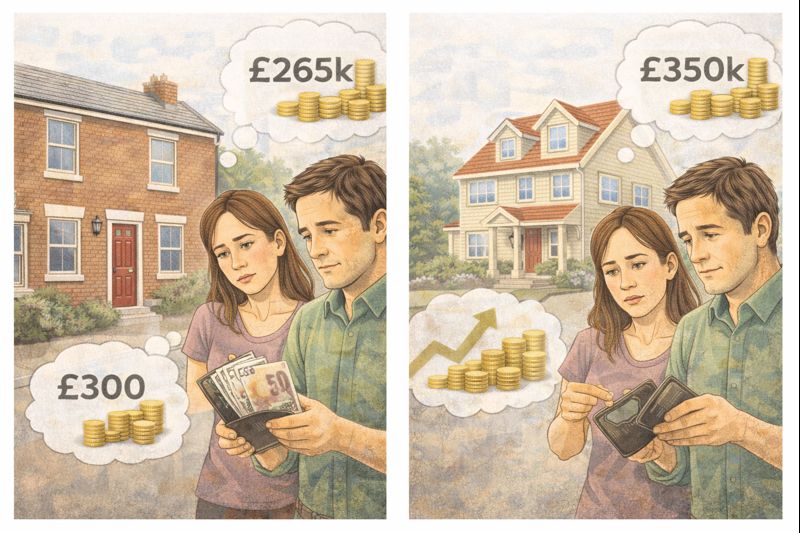

He explained that he currently lives in a housing association flat. After clearing his debts, he is finally able to save, but only around £300 a month. At that pace, he feels trapped. He worries that by the time he reaches his mid-30s, he will still be renting with very little to show for it. Home ownership feels completely out of reach.

Moving in with his grandmother would change everything financially. Instead of saving £300 a month, he could save around £1,300. In just two years, that could mean £20,000 in savings, a real deposit, and a realistic shot at buying a home. From a purely financial point of view, the difference is enormous.

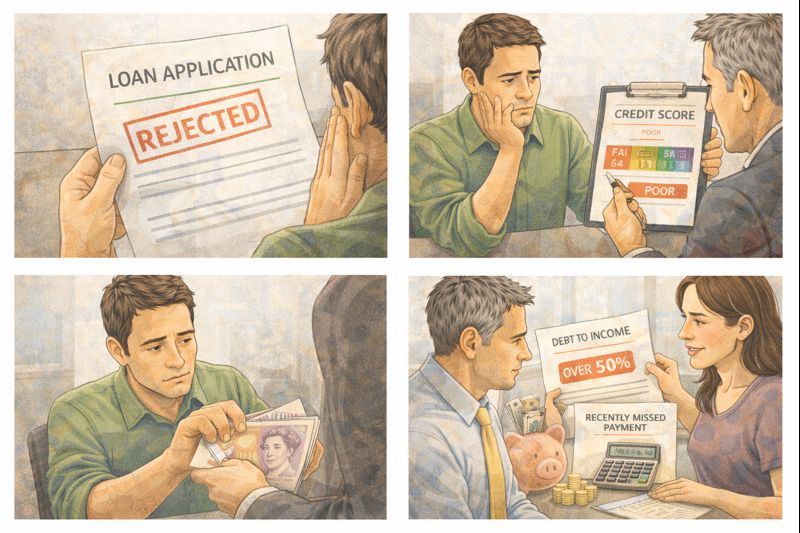

The problem is the risk. His grandmother is nearly 80 and unwell. There is no certainty about how long the arrangement would last. If her health deteriorated quickly, he could be forced to move out with little notice and scramble to find somewhere to live. That uncertainty is what makes the decision so hard.

He also pushed back strongly against people telling him to “never give up” his housing association flat. From his perspective, the flat does not lead anywhere. It is in a rural area, so Right to Buy is not an option. He sees no path from that tenancy to ownership. In his mind, staying means renting forever, having nothing to pass on to future children, and never building real security.

This is where the issue becomes bigger than one person’s choice. It reflects a wider tension between security now and opportunity later.

Housing association tenancies offer something incredibly valuable that is easy to overlook: stability. Rent is usually lower than the private market. Eviction risk is low if you follow the rules. You have a safety net. That stability has real worth, especially for someone who has only just cleared debt. It protects you from sudden homelessness, rising rents, and the stress of constant moving.

But stability does not automatically mean progress. For someone who wants to own a home, build equity, and leave something behind, a tenancy that can never convert into ownership can feel like a dead end. That feeling is very real, and it is shared by many young renters across the UK.

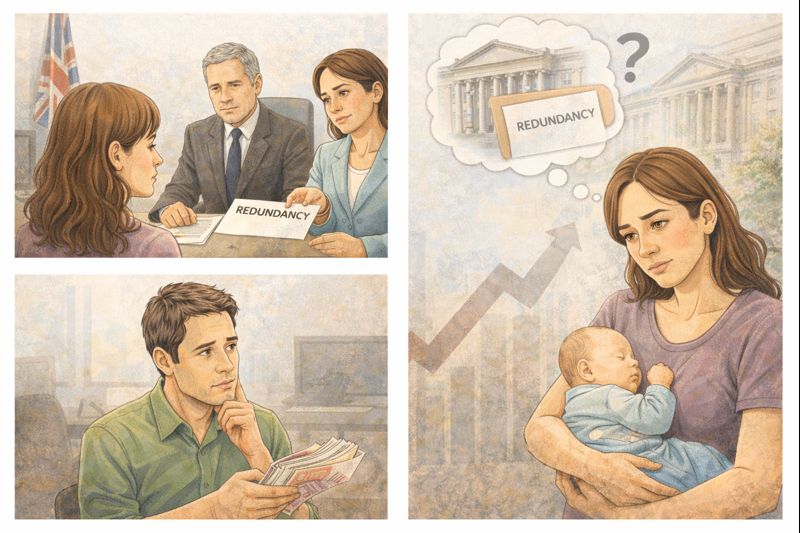

Moving in with an elderly relative can make financial sense, but it is not just a money decision. There are emotional, practical, and ethical layers. Living with someone who is ill may involve informal caring, emotional strain, and a very different lifestyle. It can also blur boundaries. Are you there as a tenant, a helper, or family support? Often, it becomes all three.

There is also the practical risk he identified. If the arrangement ends suddenly, having given up a secure tenancy could leave him exposed. Finding a new rental quickly, especially with rising rents and high competition, may be difficult and expensive. The money saved could disappear faster than expected.

At the same time, the frustration he expressed about “renting forever” taps into a generational fear. Many young people feel that if they do not take bold or uncomfortable steps, they will simply never catch up. Saving £300 a month feels responsible, but painfully slow. Saving £1,300 a month feels like a rare chance to change trajectory.

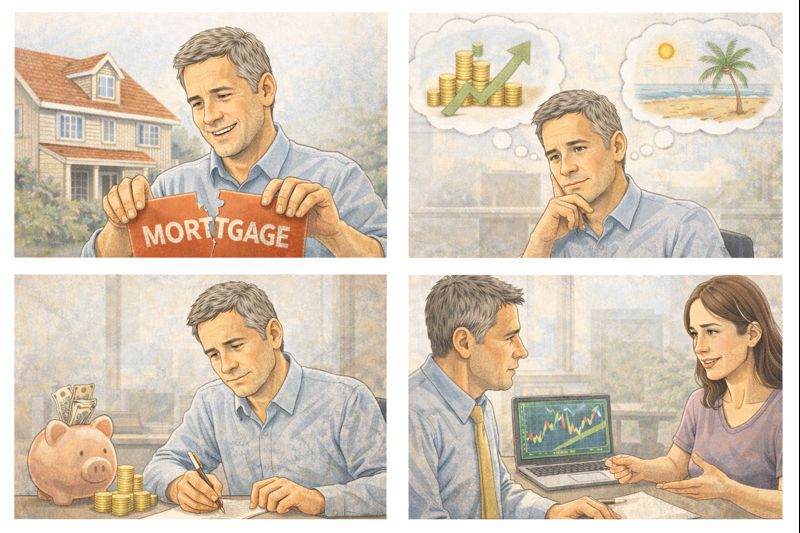

What often gets lost in these conversations is that this does not have to be an all-or-nothing mindset. Some people in similar positions look for ways to reduce risk while still increasing savings. That might mean staying registered with the housing association, understanding re-housing options, or building a larger emergency fund before making the move. It might mean treating the time with a relative as a short, defined saving sprint rather than an open-ended plan.

It is also important to challenge one assumption gently. Renting does not automatically mean having “nothing” or leaving nothing behind. Financial security can come from savings, pensions, and investments as well as property. Home ownership is powerful, but it is not the only form of stability or legacy. That said, wanting a home of your own is not wrong, unrealistic, or selfish. It is a deeply human goal.

This decision ultimately comes down to risk tolerance. Staying where he is offers safety but slow progress. Moving in with his grandmother offers speed but uncertainty. Neither choice is stupid. Both have costs.

What makes this situation especially hard is that time matters. At 25, a two-year saving window can be life-changing. At the same time, losing a secure home at that age can be destabilising if things go wrong.

For anyone reading this in a similar position, the real question may not be “is it worth the risk?” but “how much risk can I manage without putting myself in danger?” Financial growth is important, but so is having a roof over your head.

Leave a comment