For many pensioners across Britain, the hope of a higher state pension feels like a long-overdue reward after years of hard work. But this week, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has firmly shut down one of the most ambitious calls for change yet a proposal that would have seen weekly payments soar to £586, with eligibility starting at age 60.

The government’s rejection has sparked widespread debate about fairness, affordability, and how much support older people truly deserve in an age of rising living costs.

What Sparked the Debate

The controversy began with a parliamentary petition created by campaigner Denver Johnson, which proposed tying the state pension directly to the National Living Wage. His idea was simple but bold: retirees should be paid as if they worked a full-time 48-hour week at £12.21 an hour — that’s about £586 per week or roughly £30,000 a year.

It wasn’t just about money; the proposal symbolised dignity. Johnson argued that people who have contributed to the country all their lives should not be forced into poverty in old age. The plan would also extend the same payments to Britons living abroad — including the roughly 450,000 retirees who currently have their pensions “frozen” because the UK doesn’t have reciprocal uprating agreements with their countries.

At first, the idea gained traction online. Nearly 19,000 people signed the petition, and many older citizens shared their frustration with how little their current pensions stretched against rising bills. But once the issue reached Westminster, the response was swift and blunt.

The Government’s Firm Rejection

In its formal statement, the DWP made its position unmistakably clear:

“The Government has no plans to make the State Pension available from the age of 60 or for it to equal 48 hours a week at the National Living Wage.”

That short sentence effectively ended hopes of a universal £586-a-week payment. Ministers said such a move would be unaffordable and could destabilise public finances. Instead, they highlighted their ongoing commitment to the triple lock, which guarantees that the state pension rises each year by whichever is highest — inflation, wage growth, or 2.5%.

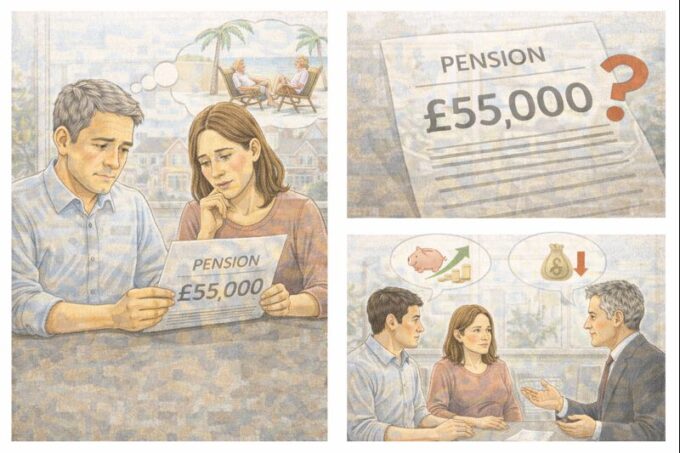

The DWP also emphasised that the state pension is designed as one pillar of retirement income, not a full salary replacement. Britain’s pension system, officials said, relies on a three-part model:

- The State Pension (basic income in later life)

- Workplace pensions (automatic enrolment)

- Private savings or investments

Ministers pointed out that the New State Pension, introduced in 2016, was meant to create a clearer and more sustainable foundation. It currently pays a maximum of £221.20 a week (£11,502 a year), though that is expected to rise to around £241 a week from April 2026 under the triple lock — still far short of the £586 proposed.

Why the Petition Struck a Nerve

To understand why this petition drew such attention, you only have to look at what many older people are facing today. Prices for essentials — food, heating, rent, transport — have risen sharply, while savings rates and private pension returns often haven’t kept pace.

For pensioners relying solely on the state pension, even small increases in energy bills or council tax can cause real distress. In that context, a guaranteed £586 a week sounds like relief — not luxury.

There’s also a psychological dimension. Many older Britons feel they’ve “paid in all their lives” through National Insurance and taxes, and therefore deserve a livable return in retirement. The petition gave voice to a wider sense of frustration that, after decades of work, people still struggle to meet basic costs.

However, while the public sentiment is understandable, the numbers behind the proposal are daunting.

The Financial Reality

Currently, the UK spends around £110 billion annually on state pensions. Analysts estimate that implementing a £586 weekly payment would almost triple that figure, pushing costs beyond £300 billion per year — more than the entire NHS budget.

The government argues that even maintaining the triple lock will see pension spending rise by another £31 billion a year by the end of this parliament. In other words, costs are already climbing fast before any radical reform.

With an ageing population and longer life expectancy, every percentage increase in pensions has a magnified impact on public finances. Ministers insist that sudden large increases would mean either higher taxes, more borrowing, or cuts to other public services such as schools and hospitals.

In a time when the economy is only gradually recovering from pandemic-era debt, those trade-offs are politically explosive.

Age of Retirement and Inter-Generational Fairness

The proposal to lower the pension age to 60 also runs counter to current policy trends. The UK’s state pension age is 66 and due to rise to 67 between 2026 and 2028, then likely 68 in the 2040s. These increases were planned to reflect longer life expectancy and the need to balance what each generation contributes versus what it receives.

The DWP defends this gradual rise as a fairness issue: younger workers are already funding pensions through their taxes, and as people live longer, it would be unsustainable for millions to draw benefits for two or more decades without adjustments.

Critics, however, say that argument oversimplifies the issue. Life expectancy gains are not evenly shared — poorer workers and those in manual jobs often die younger, meaning they benefit less from the system than professionals who live longer. Lowering the pension age could, some argue, restore fairness for those who have spent their lives in physically demanding roles.

Support That Already Exists

To soften the blow of rejection, the DWP listed several forms of assistance already available to pensioners:

- Pension Credit, which tops up the income of the poorest retirees and opens doors to further help with council tax, energy bills, and TV licences for the over-75s.

- Winter Fuel Payments for pensioners with incomes up to £35,000, ensuring the majority get heating support.

- The Warm Home Discount, Housing Benefit, and Discretionary Housing Payments for those struggling with rent.

- Extra allowances for disability and long-term illness, such as Attendance Allowance and Personal Independence Payment.

Officials also highlighted the newly created Pensions Commission, tasked with reviewing whether today’s system will provide adequate living standards for future retirees.

Yet campaigners say these measures feel piecemeal — helpful, but not transformative. The central question remains: should the state pension itself be more generous, given the wealth of the nation and the hardships many elderly face?

The Triple Lock: Popular but Costly

The triple lock is the government’s shield in this debate, and also its headache. Introduced in 2010, it was designed to stop pensions falling behind wages or prices. Every April, the state pension rises by the highest of the following three:

- Inflation (CPI),

- Average earnings growth, or

- 2.5%.

Next year’s increase, based on current data, is projected at around 4.7%, lifting the new state pension to roughly £241.05 a week (£12,534 a year). That’s good news for retirees — but expensive for taxpayers.

Economists warn that the triple lock, while politically untouchable, could become financially unstable if wage or inflation spikes continue. Some experts suggest a “double lock” (linking only to inflation or earnings) might be fairer long-term, though no government dares to propose it outright.

The Human Side of the Debate

Behind the spreadsheets are real lives. Rising energy costs and grocery prices mean many older Britons are cutting back skipping meals, switching off heating, or living in damp homes to save money.

Charities like Age UK have repeatedly warned that the state pension alone is not enough to guarantee a decent standard of living. They estimate that roughly two million pensioners live in poverty in the UK. For them, a jump to £586 a week would be life-changing, not extravagant.

On the other hand, wealthier pensioners with private incomes would also benefit from the same increase — raising questions about whether universal rises are the fairest approach. Some analysts argue that resources should instead target those who need them most, through Pension Credit and means-tested help.

What Happens Next

The petition remains open, and if it reaches 100,000 signatures, Parliament’s Petitions Committee must consider scheduling it for debate. While debates don’t guarantee policy change, they often spark media attention and can nudge ministers toward compromise.

Even without formal change, public pressure sometimes influences how future budgets are shaped. Chancellor Rachel Reeves will confirm next year’s pension and benefit uprating in the Autumn Budget on November 26, and all eyes will be on whether she hints at broader reform.

Could There Be a Middle Ground?

If tripling the pension overnight is unrealistic, could a softer path exist? Experts suggest several possibilities:

- Gradual increases over a decade, tied to economic growth, rather than a one-off leap.

- Enhanced Pension Credit to ensure no retiree falls below a genuine living-wage threshold.

- Flexible retirement options, allowing early partial pensions at 60 for those in manual or health-limiting jobs.

- Automatic enrolment expansion, encouraging higher private savings while the state provides a secure base.

Such ideas won’t grab headlines like “£586 a week,” but they might bridge compassion and realism.

Public Reactions

Reactions to the DWP’s statement have been sharply divided online. Many older citizens accuse the government of hypocrisy pointing to billions spent elsewhere while pensioners “count pennies.” Others, including younger taxpayers, argue that tripling pensions would be unfair and fiscally reckless.

Typical comments under news posts read:

“After paying tax for 45 years, is £586 too much to ask for a bit of comfort in old age?”

and equally,

“I can barely afford rent and student loans — why should I fund £30k pensions for everyone over 60?”

These opposing sentiments reveal how deeply inter-generational tensions run.

Where Britain Stands Among Other Nations

Compared to other developed countries, the UK’s state pension is relatively modest. The OECD ranks it among the lowest replacement rates (the proportion of previous earnings replaced by the state pension).

Countries like the Netherlands and Denmark offer higher state-backed pensions, but they also collect larger payroll contributions and operate more collective savings schemes. In contrast, Britain relies more heavily on individual and employer pensions.

This comparison gives weight to both sides of the argument: campaigners can claim the UK underpays its pensioners, while ministers can counter that a larger universal pension would require far higher taxes or contribution rates.

The Bigger Picture

At its core, this debate isn’t only about numbers — it’s about identity and fairness. How a nation treats its elderly says much about its moral compass.

Advocates for a universal £586 payment argue that no senior citizen in a wealthy country should worry about heating or food. The government’s response, however, stresses stewardship — the duty to manage national resources responsibly for all generations.

Neither side is entirely wrong. Compassion without fiscal realism is unsustainable; austerity without empathy is unjust.

Leave a comment