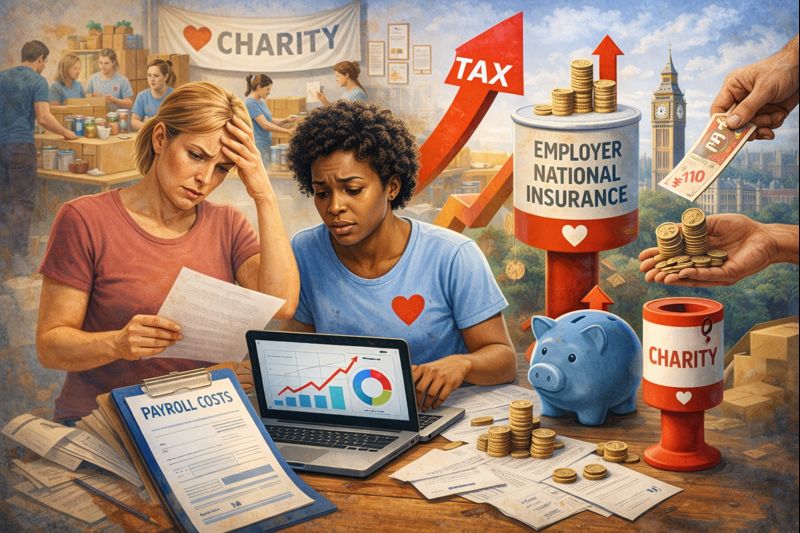

Charities across the UK are warning that recent and upcoming changes to employer costs could quietly force them to pay much more in tax, putting pressure on services that millions of people rely on. New analysis suggests that rises linked to National Insurance and employment-related expenses could significantly reduce the money charities have available for frontline support, even though they are not-for-profit organisations.

Unlike private companies, charities do not exist to make money. Most rely on public donations, grants, and fundraising to cover their costs. When employment expenses rise, charities cannot simply increase prices to cover the difference. Instead, they are often forced to cut back on services, reduce staff hours, or delay important projects.

One of the biggest concerns is employer National Insurance contributions. Employers are required to pay National Insurance on wages above a certain threshold, and even small changes to rates or thresholds can have a large impact when applied across an organisation with many staff. For charities that employ carers, support workers, outreach staff, and administrators, wage costs already make up a large part of their budgets.

Recent policy changes and frozen thresholds mean that charities are paying more employer National Insurance overall, even if wages have not increased dramatically. As salaries rise slightly to keep up with living costs, more of each employee’s pay becomes subject to National Insurance. This increases the amount charities must pay to HM Revenue & Customs without any increase in funding.

Charity leaders say this creates a hidden tax burden. While charities may not pay corporation tax in the same way as businesses, higher employer costs have a similar effect. More money flows out to the tax system, leaving less available for charitable work. Some describe it as a “stealth tax” on organisations that exist to help society’s most vulnerable people.

The impact is particularly severe for charities working in areas such as social care, homelessness, disability support, mental health, and youth services. These organisations often rely on large numbers of staff delivering services directly to the public. Even small increases in employer costs can quickly add up to tens or hundreds of thousands of pounds a year.

Many charities are already under pressure from rising demand. The cost-of-living crisis has increased the number of people needing food banks, housing support, debt advice, and mental health services. At the same time, donations have become less predictable as households struggle with their own rising bills.

This combination creates a difficult situation. Charities are being asked to do more, but with fewer resources. When employer costs rise, there is often no easy way to absorb them. Unlike local authorities or private companies, charities have limited reserves and little room to borrow.

Smaller charities are especially vulnerable. Large national charities may be able to spread costs across different programmes or draw on reserves. Smaller local organisations, often deeply rooted in their communities, may not have that flexibility. For some, a modest increase in National Insurance costs could be the difference between staying open and shutting down.

There is also concern about the knock-on effect on staff. Many charity workers already earn relatively low wages compared to similar roles in the private sector. Charities want to pay staff fairly and keep up with the cost of living, but rising employer costs make this harder. In some cases, organisations may be forced to freeze pay, cut hours, or leave vacancies unfilled.

This can lead to burnout and higher staff turnover, which affects service quality. Vulnerable people who rely on consistent support may see more disruption as experienced staff leave and programmes are scaled back.

Another issue highlighted by analysts is that charities often deliver services on behalf of the government through contracts or grants. These funding arrangements are not always updated quickly to reflect rising employer costs. As a result, charities can end up absorbing the extra cost themselves, effectively subsidising public services through their own limited budgets.

Charity sector groups argue that this is unsustainable. They say that if the government expects charities to continue delivering essential services, funding models must take full account of employment costs, including National Insurance and pension contributions.

Some charities are now reviewing their staffing models as a result. This may include relying more on volunteers, reducing opening hours, or limiting the number of people they can support. While volunteers play a vital role, many services require trained professionals, and volunteer support cannot always replace paid staff.

The situation also raises concerns about fairness. Charities argue that it does not make sense for organisations that exist to provide public benefit to face growing tax-like pressures that reduce their ability to help. They say the current system risks undermining the very services that prevent problems from becoming worse and more expensive for society in the long run.

Supporters of the current system argue that National Insurance funds important public services, including healthcare and pensions. However, critics counter that charities already save the government money by stepping in where public services are stretched. Increasing their costs could ultimately lead to higher pressure on the public sector.

Some sector leaders are calling for targeted relief. Suggestions include higher National Insurance thresholds for charities, temporary exemptions, or additional grant funding to cover rising employer costs. Others want clearer long-term planning so charities can budget with confidence rather than reacting to year-by-year changes.

Public awareness is also an issue. Many donors assume that charities operate separately from the tax system and may not realise how much employer costs affect their ability to deliver services. Greater transparency could help people understand why some charities are asking for more support or changing how they operate.

As financial pressures continue to build, the charity sector warns that without action, the impact will be felt not only by organisations themselves but by the millions of people who depend on them. Reduced services, longer waiting lists, and fewer outreach programmes could become more common.

The analysis makes one thing clear. While charities may not be taxed like businesses, changes to National Insurance and employer costs are having a similar effect. Unless these pressures are addressed, charities risk being quietly squeezed at a time when their work is more important than ever.

Leave a comment