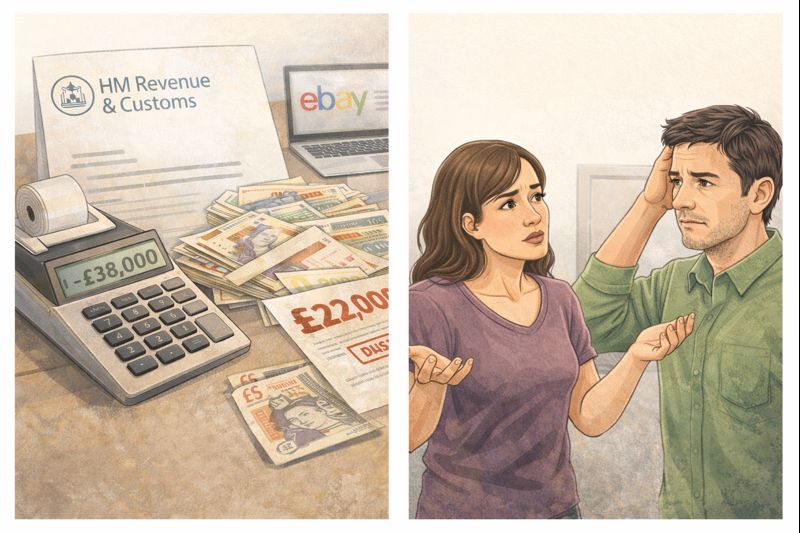

A growing number of people are finding themselves caught up in unexpected tax disputes after online selling accounts are linked to their name, even when the activity was not theirs. One recent case highlights a tricky question many face when dealing with HMRC: when explaining what happened, how honest is too honest?

In this situation, HMRC raised a tax assessment after identifying significant online sales linked to an individual’s eBay account. The sales were substantial, with one year exceeding £10,000 in revenue, enough to trigger close scrutiny. The problem was that the sales were not actually carried out by the account holder.

After appealing, the individual explained that a third party — their former partner — had used the account, and that the proceeds were passed on to that person. Bank statements were provided showing money moving in and out, and HMRC accepted the appeal in principle, pausing enforcement while they reviewed the evidence.

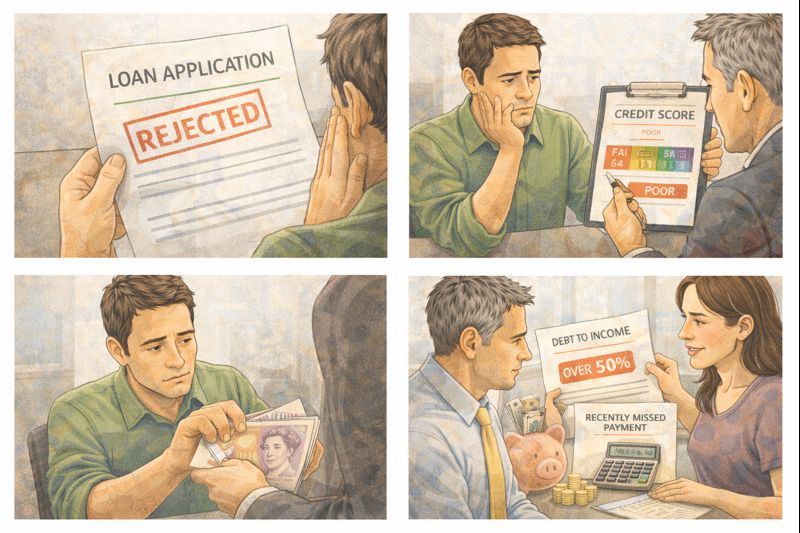

However, HMRC then came back with further questions. They asked why the other person had used the account in the first place, and requested more detailed evidence showing exactly how the money flowed across the relevant tax years.

This is the point where many people start to worry.

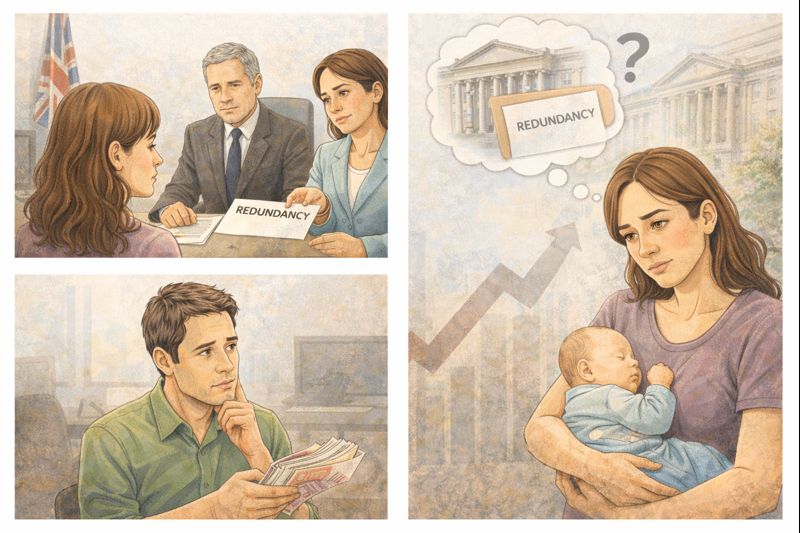

The underlying reason for the account arrangement is sensitive. The ex-partner was working for a brand at the time and was selling items they had obtained as freebies or through staff discounts. Selling under their own name could have led to disciplinary action or dismissal, so they used someone else’s eBay account instead. The ex-partner no longer works there, but the concern remains: does explaining this fully risk turning a tax query into something more serious?

The fear is understandable. HMRC’s current focus is on tax attribution — who earned the income and who should be taxed on it. But once additional context is provided, especially context that hints at breaches of employment terms or potential misuse of staff benefits, people worry it could escalate into allegations of fraud or trigger referrals to other bodies.

So what is the safest and most effective approach?

Tax advisers generally stress one key principle: answer the question HMRC has asked, but do not volunteer unnecessary detail that is outside the scope of their enquiry.

HMRC is not, at this stage, asking whether employment rules were broken or whether the third party breached an employer’s internal policies. Their concern is whether the income should be taxed on the account holder or someone else, and whether the evidence supports that position.

In this case, HMRC already appears open to accepting that the sales were not the account holder’s income. That is a positive sign. The follow-up questions are typical when HMRC wants to be satisfied that the explanation is genuine and consistent, rather than an attempt to reassign income after the fact.

When HMRC asks why someone else used the account, they are usually trying to establish control and benefit. Who controlled the listings? Who decided pricing? Who handled customer messages? Who kept the money? These factors matter far more for tax purposes than the personal or employment reasons behind the arrangement.

A high-level explanation is often enough. For example, stating that there was an informal arrangement where a third party used the account for convenience, that the account holder did not run the business activity, did not set prices, did not manage sales, and did not retain profits. Emphasising lack of control and lack of benefit goes directly to the tax issue.

Explaining that the money was passed on, supported by bank statements showing regular transfers, strengthens that position. The fact that the third party is on a lower tax rate is relevant context, but it should be presented carefully, as HMRC can be sensitive to arrangements that appear to reduce overall tax.

What advisers usually caution against is introducing motivations that could raise unrelated red flags unless HMRC specifically asks. Saying that the account was used to avoid workplace consequences does not help establish tax ownership of the income. It also opens up questions that HMRC does not need to answer in order to resolve the tax dispute.

That does not mean being dishonest. It means being precise.

There is a difference between withholding relevant information and not volunteering extraneous detail. If HMRC were to directly ask whether the arrangement was intended to conceal sales from an employer, that would require careful handling and likely professional advice. But if the question is simply why the account was used, an answer framed around convenience, informality, and separation of finances is usually sufficient.

Another important factor is consistency. HMRC will compare explanations against evidence. If bank statements show money being transferred promptly and regularly, that supports the claim that the account holder was acting as a pass-through, not earning the income. Any retained amounts should be clearly explained, especially if they relate to shared expenses or reimbursements, as already mentioned.

It is also worth noting that HMRC’s powers are focused on tax. While they can refer cases to other departments if they uncover evidence of serious wrongdoing, this is not automatic and usually requires clear indicators of deliberate tax evasion or criminal behaviour. A domestic arrangement between partners, even if ill-advised, does not automatically meet that threshold.

That said, the sums involved are not trivial. Revenue over £10,000 brings the case well above casual selling territory, which is why HMRC is digging deeper. This is also why clarity and structure in responses matter.

Many advisers would recommend responding in writing, keeping answers factual, calm, and narrowly focused. Where possible, attaching clear timelines, summaries of transactions, and explanations of roles can prevent further rounds of questioning.

If uncertainty remains, or if HMRC’s questions start to drift beyond tax attribution into intent or concealment, seeking professional tax advice becomes crucial. A tax adviser can help frame responses correctly and step in if the enquiry escalates.

For now, the situation appears manageable. HMRC has paused action and accepted the appeal in principle, which suggests they are open to being persuaded. The goal is to maintain that trajectory by answering what is asked, proving who earned the income, and avoiding unnecessary complications.

Cases like this are becoming more common as HMRC increases its use of online marketplace data. Many people lend accounts to partners or family members without thinking about long-term consequences, only to face problems years later when algorithms flag discrepancies.

The key lesson is that when HMRC comes calling, clarity beats over-explanation. Stick to the tax facts, show the money trail, and remember that you are not required to build a case against yourself for issues HMRC has not raised.

Leave a comment