When illness arrives or a long-term condition becomes part of daily life, the first shock is often financial. Wages dip, costs rise, and suddenly the simplest tasks getting to appointments, heating the home when you’re unwell, buying equipment carry a price tag. The UK benefits system was built to steady people in exactly these moments, but the rules are spread across different schemes with different tests. Some payments are there to replace income when you can’t work.

Others are designed to help with the extra costs of disability, regardless of earnings. Some are specific to Scotland or Northern Ireland; others are UK-wide. And a few are there for the people who do the caring. This report lays out the map in plain language so you can find your route quickly: what each benefit is for, who typically qualifies, how it interacts with the rest, and the smart steps to take before you apply.

Think of the system as a set of layers. At the top are short-term payments if you’re off sick from a job. Underneath that are the disability benefits that pay for the additional costs of living with an impairment or long-term condition washing, dressing, preparing food, moving around, planning journeys, using aids or supervision. Alongside sit the means-tested schemes for low-income households, including help with rent and council tax.

There’s a separate track if your condition is tied to your work. And around the edges live the overlooked but powerful supports: Blue Badge, Motability, concessionary travel, and local grants for equipment or home adaptations. Most people will build a package from more than one of these. The trick is understanding what each scheme measures and gathering evidence that speaks their language.

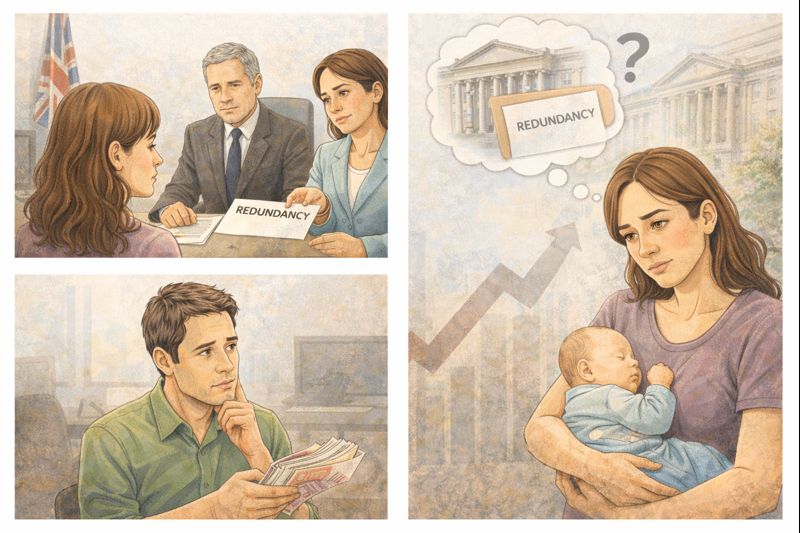

Start with the obvious: if you’re employed and too ill to work, your employer may pay Statutory Sick Pay (SSP) for a limited period (up to 28 weeks) as long as you earn above the minimum weekly threshold. Think of SSP as a bridge; it keeps some income flowing while you’re off, but it isn’t designed for long haul. If you expect to be off longer or you don’t hit the earnings requirement, you look next to Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) or Universal Credit (UC), depending on your National Insurance record and your household income. A smart move is to line up ESA before SSP ends so there’s no gap between the last sick-pay payslip and your first ESA payment. Keep your fit notes and any HR emails in one folder; if you end up applying for UC as well, you’ll need a clean timeline of what happened and when.

ESA divides into what’s often called “New Style” ESA—based on recent National Insurance contributions—and the older income-related version, which has largely been replaced by Universal Credit for new claims. With ESA and UC, the Department for Work and Pensions (or the relevant administration in Northern Ireland) will usually want a Work Capability Assessment. That’s not a test of your diagnosis; it’s a test of what you can do reliably.

Can you sit, stand, and focus for long enough to work? Can you move around safely? Do you have episodes that would make work unsafe? The assessment is built around descriptors—specific activities—so your job is to translate your daily reality into those markers. For many people, the assessment outcome decides whether an extra element is added to their UC or whether ESA continues at a higher rate. If the words “work-related activity” sound ominous, remember: the system can exempt people whose conditions make such activity unreasonable. Evidence is everything.

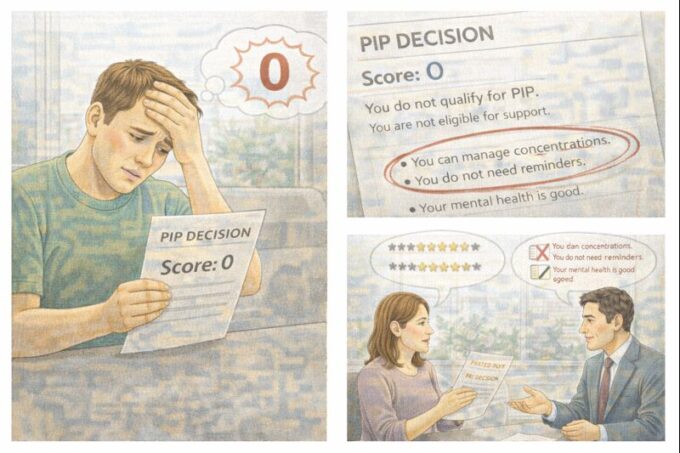

Running alongside ESA and UC is the part of the system most families under-use: benefits that pay for the extra costs of disability. For working-age adults in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, that’s Personal Independence Payment (PIP). In Scotland, it’s Adult Disability Payment (ADP). These are not about earnings. You could be on a high salary and still get PIP/ADP if your condition meets the criteria, because these payments are meant to offset the costs of daily living and mobility needs—extra heating, taxis, carers, equipment, and the time it takes to do basic things safely.

Both PIP and ADP have two strands: daily living and mobility, each with two levels of award. Points are scored based on those descriptors—preparing food, washing, dressing, managing medication, communicating, planning a journey, moving around. You don’t get points for a diagnosis; you get points for what your condition means in practice, day after day. That’s why the strongest applications read like a photograph of a bad day, not a list of Latin terms. If you use aids, say so. If your pain or fatigue stops you finishing tasks to a safe standard or you need supervision to avoid falls, explain it in real examples.

For children under 16, the equivalent is Disability Living Allowance (DLA). This supports families where a child needs more care or supervision than their peers or has serious mobility problems. DLA can be pivotal: it can increase other benefits, unlock travel concessions, and open the door to Motability if the mobility component is high enough. At State Pension age, the picture changes: PIP generally closes to new claims, and Attendance Allowance becomes the relevant benefit in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, the pension-age equivalent is Pension Age Disability Payment. These are focused on personal care needs rather than mobility, but they’re non-means-tested and tax-free.

There’s usually a six-month qualifying period unless the person is terminally ill, when fast-track rules apply. A lot of older people assume they “don’t want to take money from the system” and leave this unclaimed. That’s often a mistake: Attendance Allowance doesn’t penalise savings and can be the difference between coping and a crisis.

Some conditions are caused by work itself: exposure to noise, chemicals, repetitive strain, or accidents on site. Industrial Injuries Disablement Benefit (IIDB) is there for those cases. It doesn’t look at your income. It asks a different question—what’s the percentage of disablement linked to that job-related cause? An assessment will grade it, and the award is tied to that rating. IIDB can sit alongside other benefits. If your story belongs in that lane, gather workplace evidence early: accident books, occupational health letters, audiology reports, consultants’ findings. People often wait years before connecting the dots; better to file a claim and let the evidence be tested than to live with doubt.

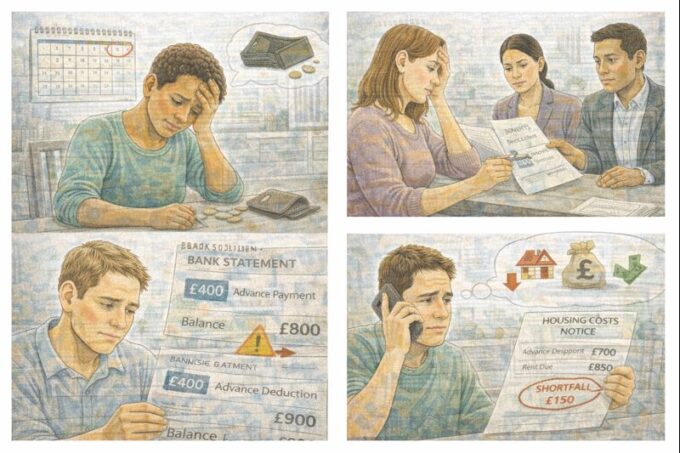

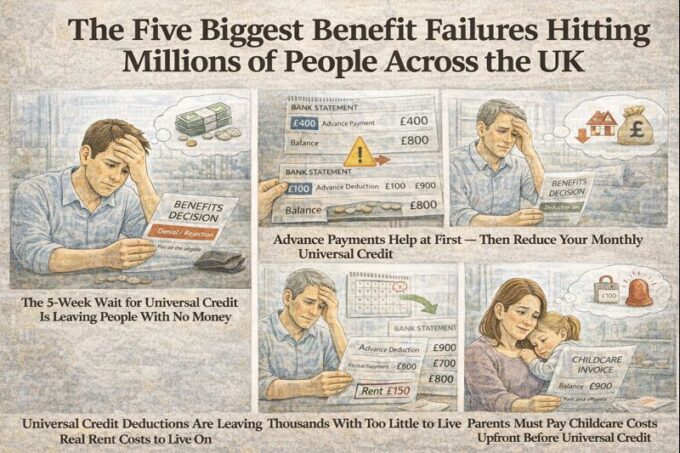

Beyond the headline schemes, there’s help that doesn’t always appear in benefit calculators but makes a tangible difference to a tight budget. Housing support now mainly runs through Universal Credit for renters, with Support for Mortgage Interest available as a loan for some homeowners. Every local authority runs a Council Tax Reduction scheme; criteria vary, but if your income has fallen or a household member is disabled, it’s worth applying.

The Blue Badge can put parking close enough to make appointments realistic. If you receive the enhanced mobility component of PIP/ADP (or the relevant legacy equivalent), Motability allows you to lease a car or scooter that fits your needs, with insurance and servicing included. Charities and councils also fund adaptations—from grab rails to stairlifts—through grants that don’t need repaying. A five-minute search on a grants database can produce leads you never knew existed.

So how do these pieces fit together without clashing? A few rules of thumb help. First, disability extra-costs benefits—PIP, ADP, DLA for children, Attendance Allowance/Pension Age Disability Payment—usually do not reduce your means-tested income benefits; in fact, your Universal Credit can go up when you receive them because the system recognises extra costs. Second, Universal Credit has replaced a lot of older income-based payments.

If you move over from a legacy benefit, some supplements from the old system won’t exist in UC (for example, the Severe Disability Premium), though transitional protection can soften the blow for some claimants moving under managed migration. Third, SSP and ESA generally can’t be paid at the same time, so plan the handover to avoid a gap. Fourth, Scotland runs its disability benefits through Social Security Scotland, not DWP, and the application style and review process are different—same core idea, different route in. Northern Ireland mirrors much of England and Wales but is administered by its own departments; practical guidance is on nidirect.

The single biggest factor in successful claims is evidence. Not fancy language. Evidence. Before you pick up a form, build a simple archive: GP letters, clinic summaries, test results, physio and occupational therapy reports, care plans, appointment lists, medication lists, and critical your own diary notes from a handful of “bad days.

Benefits decision-makers work to definitions like “can you do this safely, to an acceptable standard, repeatedly, and in a reasonable time?” If you can shower only when someone is nearby because you’ve slipped before, that is “needing supervision.

If you can prepare food only when everything is laid out and you rest twice before finishing, that is a real-world time and safety issue, not a preference. Where memory or mental health is involved, explain what happens without prompts burnt pans, missed meds, getting lost. Admissions like this aren’t weaknesses; they’re the facts that match the descriptors the system is scored against.

When you’re applying for more than one benefit, keep the story consistent. If your PIP form says you need daily supervision in the bathroom but your UC journal claims you can work eight-hour shifts without breaks, you’ll invite delay and doubt. That doesn’t mean you must present yourself as helpless—it means you describe limits consistently across all claims. If you do something on a very good day with extraordinary effort and then spend the next two days in bed, say so. Decision-makers need to know what is sustainable, not what is occasionally possible.

What if you’re refused or the award is lower than you think it should be? Read the decision letter line by line. It will say which descriptors the assessor believed you met. If they’ve misread your evidence or missed key facts, ask for a Mandatory Reconsideration and send clearer proof. If that fails, appeal to a tribunal. The tribunal won’t punish you for challenging a decision; a large share of PIP and ESA appeals succeed because the panel hears a fuller account and sees better evidence the second time. If paperwork overwhelms you, disability advice charities and Citizens Advice can help shape the story and point to the right descriptors.

A few practical scenarios make this concrete. Picture a warehouse worker in Cardiff who develops severe back pain. She earns above the threshold, so she goes on SSP while awaiting scans. At ten weeks, it’s clear she won’t be fit in time. She submits a New Style ESA claim to start as soon as SSP ends and opens a Universal Credit claim to help with rent.

In parallel, she applies for PIP, focusing on the “preparing food,” “washing,” and “moving around” activities she uses a perching stool in the kitchen and needs help getting in and out of the bath. The PIP decision arrives with daily living at the standard rate and mobility at the standard rate. That award increases her UC calculation and makes her eligible for the Blue Badge. A small council tax reduction drops through a month later. The puzzle pieces don’t collide; they reinforce each other.

Or take a family in Glasgow with an autistic child who has challenging behaviour and needs supervision to stay safe. They apply for DLA for children, carefully explaining the day-and-night supervision beyond what’s typical for that age. With an award in place, their Universal Credit rises and they secure a companion bus pass that saves real money on weekly travel. Because they live in Scotland, the parents know that when their child becomes 16, the replacement benefit won’t be PIP but Adult Disability Payment. They start gathering school and health evidence early so the transition is less stressful.

Or picture a retired engineer in Belfast who struggles with dressing, bathing, and getting up steps. He assumes he’s “managing.” His daughter persuades him to apply for Attendance Allowance. They keep a two-week diary showing the help he needs, and the award arrives at the higher rate. That payment covers a few hours of paid care each week, reduces his anxiety about asking family, and crucially signals to the council that he qualifies for a bathroom adaptation grant. Suddenly the layout of his home works for him again.

These stories share a pattern: the right benefit for the right job, the right evidence at the right time. If you’re an employee and first go off sick, start with SSP and plan the handover to ESA/UC. If your condition brings extra costs, don’t ignore PIP/ADP or DLA for children or Attendance Allowance; they can transform a budget. If income is tight, UC ties in housing support and may add a health element after the Work Capability Assessment. If the job caused the damage, investigate IIDB. Don’t forget the peripheral supports that make independence possible: Blue Badge, Motability, travel concessions, council tax help, grants for equipment and home changes. Thread it all together with proof, not guesswork.

Two last points. First, geography matters. Scotland runs ADP and its pension-age replacement through Social Security Scotland with different processes, terminology and review culture to DWP. Northern Ireland has its own administration and guidance via nidirect. Wales follows the England model but your local council decides your council-tax scheme.

Always check the nation-specific page before you press submit. Second, rates change. This article avoids quoting pound-and-pence figures beyond basic thresholds because amounts are updated each year; use the official sites and calculators on the links below to pull the current numbers on the day you claim.

If you read nothing else, take this checklist with you: keep all medical letters, fit notes and reports; write down the reality of a bad day in ordinary language; match your explanations to the activities each benefit measures; apply for more than one benefit if you’re eligible; and, if you’re refused, challenge it with clearer evidence rather than giving up.

The system can be slow and sometimes frustrating, but it is there to keep people afloat when health knocks them sideways. Make it work for you.

- GOV.UK — Benefits and financial support if you’re disabled or have a health condition

https://www.gov.uk/browse/benefits/disability - GOV.UK — Benefits and financial support if you’re temporarily unable to work

https://www.gov.uk/browse/benefits/unable-to-work - GOV.UK — Financial help if you’re disabled: Disability and sickness benefits

https://www.gov.uk/financial-help-disabled/disability-and-sickness-benefits - GOV.UK — Disability Living Allowance (DLA) for children: How to claim (Easy Read PDF)

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6437d079db4ba9000c448e07/how-to-claim-dla-for-children-easy-read.pdf - Citizens Advice — Check what benefits to claim if you’re sick or disabled

https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/benefits/sick-or-disabled-people-and-carers/benefits-for-people-who-are-sick-or-disabled/ - MoneyHelper (MaPS) — What disability and sickness benefits can I claim?

https://www.moneyhelper.org.uk/en/benefits/benefits-if-youre-sick-disabled-or-a-carer/what-disability-and-sickness-benefits-can-i-claim - MoneyHelper — Universal Credit for sick or disabled people

https://www.moneyhelper.org.uk/en/benefits/benefits-if-youre-sick-disabled-or-a-carer/universal-credit-for-disabled-people - Working Families — What can I claim if I am too sick to work?

https://workingfamilies.org.uk/articles/what-can-i-claim-if-i-am-too-sick-to-work/ - Working Families — A Guide to Benefits for Disabled Adults

https://workingfamilies.org.uk/articles/a-guide-to-benefits-for-disabled-adults/

Leave a comment