When people first apply for Universal Credit and realise they must wait weeks for their first payment, many are offered something called an Advance Payment. At that moment, it can feel like a lifeline. Rent is due, food is running out, and bills cannot wait. The idea of getting money quickly sounds like the only way to survive.

For some people, the advance really does help in the short term. It can prevent immediate hunger, stop electricity from being cut off, or help cover rent during those first difficult weeks. But what is less clear at the start is what happens after the advance is paid. For many claimants, the help they received early on later becomes another long-term problem.

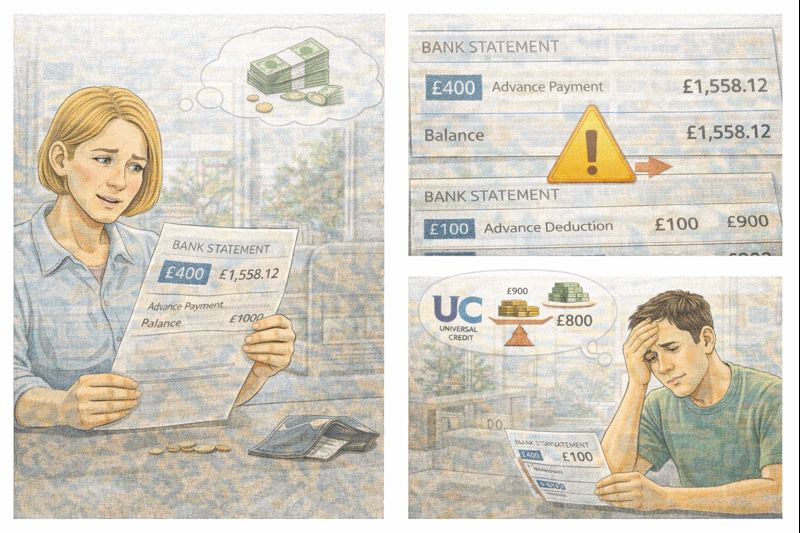

An Advance Payment is not extra money. It is not a grant. It is a loan taken from future Universal Credit payments. That fact is often understood in theory, but not fully felt until repayments begin.

The system works like this. When someone applies for Universal Credit, they are assessed for how much they are likely to receive each month. Based on that estimate, they may be offered an advance covering some or all of their expected first payment. This money is usually paid quickly, sometimes within a few days. For someone with no income at all, this can feel like relief.

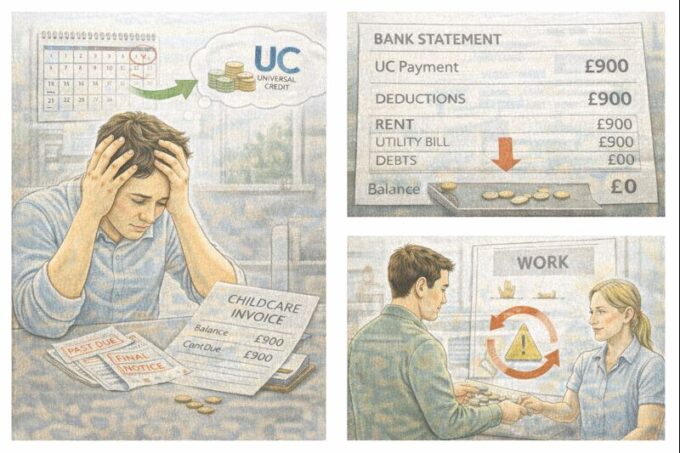

However, once regular Universal Credit payments begin, the advance must be paid back. Repayments are taken automatically from each monthly payment before the money reaches the claimant. This means people receive less than their full entitlement every month until the advance is cleared.

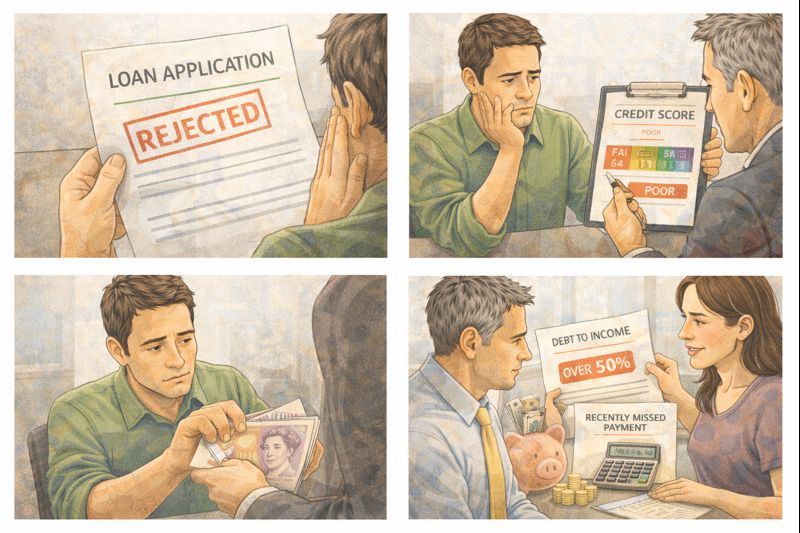

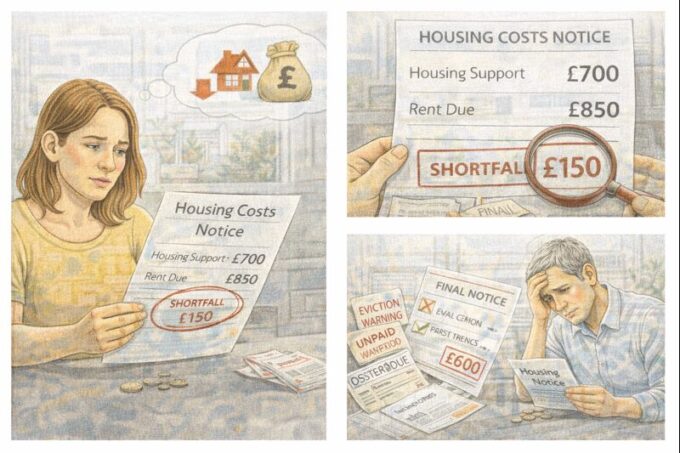

For many households, this reduction in income comes at a time when they are already trying to recover from the financial damage caused by the five-week wait. Debts may have built up. Rent arrears may have started. Credit cards or overdrafts may already be in use. The reduced Universal Credit payment can make it very difficult to catch up.

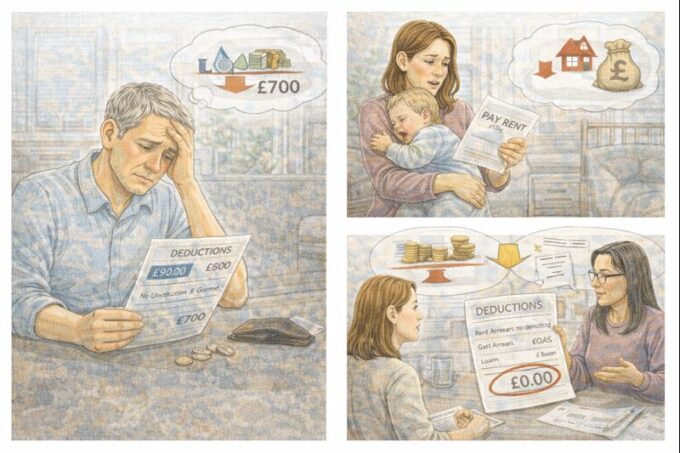

One of the biggest problems with advance repayments is how little control claimants feel they have once deductions start. The money is taken automatically. It happens before bills are paid, before food is bought, before any other choices can be made. For people living on tight budgets, even a small deduction can tip things from difficult into impossible.

Many claimants say they did not fully understand how much would be taken each month or how long repayments would last. Some expected the deduction to be small or short-term. In reality, repayments can continue for many months, sometimes up to two years, depending on the amount borrowed and the repayment period agreed.

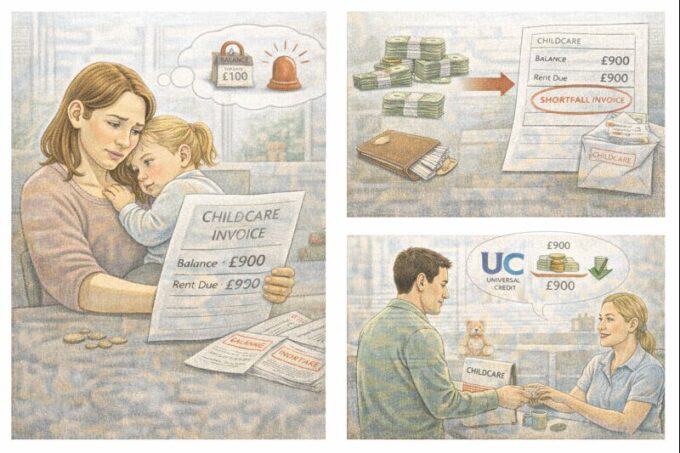

This can leave people feeling trapped. They needed the advance to survive at the start, but now that same decision is making it harder to live month to month. Some describe it as being pushed into debt by the system designed to support them.

The situation is especially hard for households with additional deductions. Universal Credit payments can also be reduced to repay other debts, such as benefit overpayments, council tax arrears, rent arrears, court fines, or child maintenance. When advance repayments are added on top of these, the total amount taken can be significant.

In some cases, people are left with far less than they need to cover basic living costs. This can lead to further borrowing, creating a cycle of debt that is difficult to escape. Instead of helping people stabilise their finances, the advance repayment system can prolong financial stress.

Another issue is that advances are often taken at a moment of crisis, when people are not in the best position to make careful financial decisions. When someone has no money for food or heating, long-term repayment plans are not their main concern. The focus is on getting through the next few days.

This is why many advice organisations argue that advances are not a true solution to the five-week wait. They shift the problem forward rather than solving it. The hardship does not disappear; it simply shows up later in the form of reduced income.

That does not mean advances are always the wrong choice. For some people, they are unavoidable. But it does mean they should be taken with caution and with a clear understanding of the consequences.

There are steps claimants can take to reduce the negative impact of advance repayments.

One of the most important is to borrow only what is absolutely necessary. It can be tempting to take the maximum amount offered, especially when facing multiple bills. But the larger the advance, the larger the monthly deductions will be later. Asking for a smaller advance can make future payments easier to manage.

Another key step is to ask for the longest possible repayment period. Spreading repayments over more months reduces how much is taken from each payment. While this means the debt lasts longer, it can make the monthly budget more manageable.

Claimants can also ask for deductions to be reduced if they are causing hardship. This is not automatic, and it may require explaining the situation clearly and providing evidence. But in some cases, reductions or pauses can be agreed.

It is also important to get independent advice early. Welfare advisers can help claimants understand their options, challenge unfair deductions, and access other forms of support that may reduce the need for borrowing.

Local support can play a crucial role here. Some councils offer emergency assistance or hardship funds that do not need to be repaid. Charities may provide food vouchers, energy support, or small grants. While these supports vary by area, they can sometimes prevent the need for a large advance in the first place.

For families with children, managing advance repayments can be particularly stressful. Child-related costs do not decrease just because income is reduced. School expenses, clothing, transport, and food all continue. When Universal Credit payments are lower than expected, parents often feel the pressure immediately.

The emotional impact of advance repayments should not be ignored. Many people feel guilt or regret for taking the advance, even though it was necessary at the time. Others feel angry or misled, believing the long-term impact was not made clear enough. These feelings can add to stress and affect mental health.

From a wider perspective, many organisations argue that the reliance on advances highlights a deeper problem within Universal Credit. If a benefit system regularly requires people to take loans just to survive the start of a claim, then something in the design is not working.

Suggestions for reform often include replacing advances with non-repayable starter payments, reducing the waiting period, or automatically protecting vulnerable claimants from large deductions. Until changes like these are made, advances will continue to be both a help and a harm.

For claimants dealing with advance repayments now, the most important thing is to stay informed and seek help. Understanding what is being deducted and why is the first step. If payments feel unmanageable, it is worth asking whether deductions can be reduced or whether additional support is available.

Taking an advance does not mean someone has failed. It means they were placed in a difficult position by the system. With the right advice and support, it is possible to manage repayments and avoid falling deeper into debt.

The key message is this: Advance Payments can help people survive the first weeks of a Universal Credit claim, but they often create longer-term pressure. Knowing the risks, asking the right questions, and getting support early can make a real difference.

Leave a comment