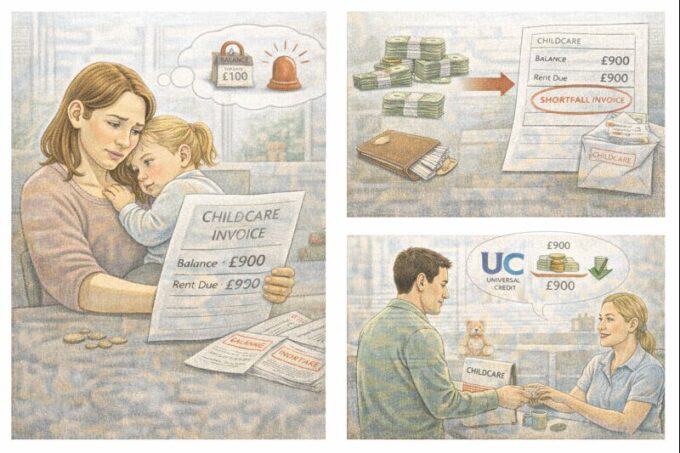

For many people on Universal Credit, housing support is supposed to make rent affordable. In reality, it often falls short. Across the UK, a growing number of claimants are finding that the amount they receive for housing simply does not match what landlords are charging. The result is a widening gap between benefit support and real rent, leaving people to cover the difference themselves — often without the money to do so.

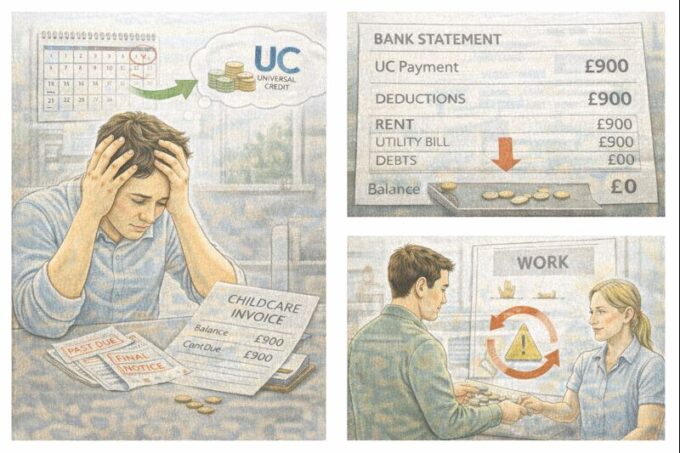

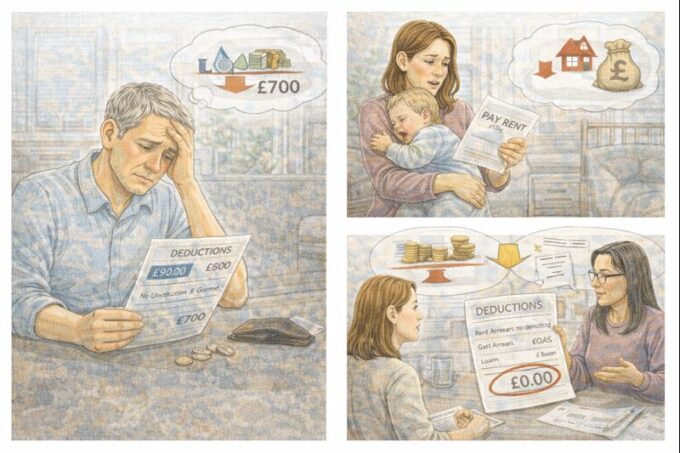

This problem affects people quietly but deeply. Rent is usually the biggest monthly expense. When housing support does not cover it, everything else in the budget comes under pressure. Food, heating, transport, and basic household items all become harder to afford. Over time, this can push people into arrears, debt, and even homelessness.

Universal Credit housing support is based on something called the Local Housing Allowance, often shortened to LHA. This sets a maximum amount of rent support based on local area rates and household size. In theory, it is meant to reflect typical rents in an area. In practice, it often does not.

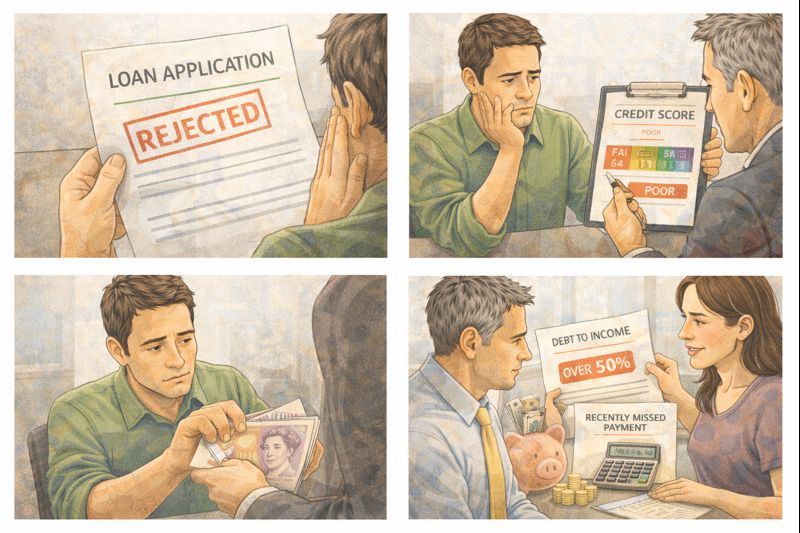

Rents in many parts of the UK have risen sharply over recent years. Private landlords have increased prices due to higher mortgage rates, rising maintenance costs, and strong demand. However, Local Housing Allowance rates have not always kept pace with these increases. When LHA stays the same but rents rise, the shortfall is passed directly to tenants.

For someone working full-time, a rent increase may be absorbed by higher income. For someone on Universal Credit, there is usually no flexibility. The benefit amount is fixed, and any shortfall must come out of money meant for living costs.

This gap is especially common in the private rented sector. Many private landlords now charge rents well above LHA limits, particularly in cities and high-demand areas. As a result, people on Universal Credit often struggle to find properties that are officially “affordable” under the system.

Some landlords simply refuse to rent to Universal Credit claimants altogether. Others accept them but charge rents that exceed housing support levels. In both cases, claimants are left with limited choices and little bargaining power.

Even social housing tenants are not immune. While social rents are usually lower, changes in circumstances, under-occupancy rules, or service charges can still create shortfalls that Universal Credit does not fully cover.

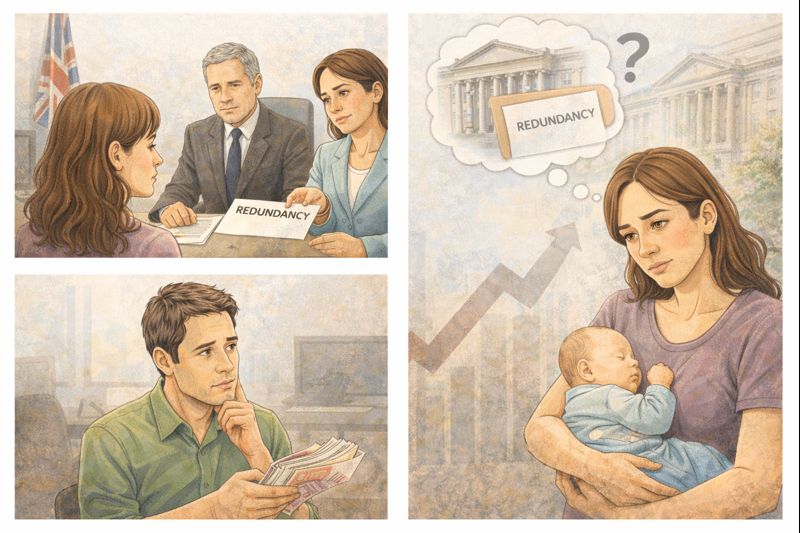

The impact of these rent gaps builds over time. At first, someone may try to manage by cutting back on food or skipping other bills. But rent is relentless. It comes every month, and arrears grow quickly. Once arrears begin, stress increases and the risk of eviction rises.

For many claimants, the situation feels impossible. They are doing everything expected of them — claiming correctly, reporting changes, attending appointments — yet they still cannot afford to live where they are.

Housing stress also affects mental health. Constant worry about rent, fear of eviction, and letters from landlords can lead to anxiety, poor sleep, and depression. For families with children, the pressure is even greater, as housing instability affects schooling, routines, and emotional wellbeing.

Another problem is how housing support is paid. Universal Credit is paid as a single monthly payment to the claimant, including housing costs. This means tenants are responsible for paying rent themselves. While this works for some, it can be difficult for people who are already struggling to budget or who have had disrupted income.

When housing support does not cover the full rent, paying the landlord in full may be impossible. Even small monthly shortfalls add up quickly. Missing one payment can trigger warnings. Missing several can lead to formal action.

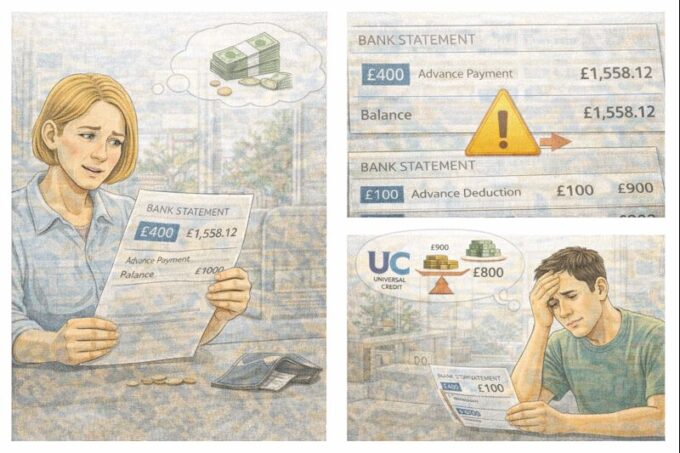

There are options available, but they are not always well understood.

One important form of help is Discretionary Housing Payments, often called DHPs. These are short-term payments from local councils designed to help people struggling with rent shortfalls. They can be especially useful when Universal Credit housing support does not meet actual rent costs.

DHPs are not automatic. Claimants usually need to apply and explain their situation. Councils decide based on local rules and available funds. While DHPs can provide relief, they are often temporary and may not cover the full shortfall long-term.

Another option is requesting an Alternative Payment Arrangement. This can include having rent paid directly to the landlord instead of going to the claimant. While this does not increase the amount of housing support, it can sometimes help prevent arrears and reduce pressure from landlords.

It is also important for claimants to check that their housing costs are being calculated correctly. Mistakes can happen, especially with shared accommodation, service charges, or changes in household circumstances. Ensuring that all eligible housing costs are included can make a difference.

Seeking advice early is critical. Housing advisers and welfare advisers can help claimants understand their options, apply for DHPs, negotiate with landlords, and challenge incorrect decisions. The earlier help is sought, the more options are usually available.

Some claimants may consider moving to cheaper accommodation, but this is often easier said than done. Affordable properties may be scarce, far from support networks, or unsuitable for health or family reasons. Moving itself costs money, which many people simply do not have.

At a system level, many organisations argue that housing support under Universal Credit needs urgent reform. They point out that tying support to outdated rent levels does not reflect real housing markets. When benefits fail to match housing costs, the system shifts the burden onto individuals who cannot absorb it.

Calls for change include updating Local Housing Allowance more regularly, increasing support in high-rent areas, and offering stronger protections against eviction for people on benefits. Until such changes happen, housing shortfalls will remain a major source of hardship.

For claimants facing this issue now, the most important steps are not to ignore the problem and not to face it alone. Check housing cost calculations, speak to the council about discretionary support, communicate with landlords early, and seek advice as soon as possible.

Struggling to cover rent while on Universal Credit is not a sign of irresponsibility. It is a sign that housing costs and benefit support are out of step. Understanding this can help people move from self-blame to seeking the help and solutions that do exist, even within a difficult system.

Leave a comment